Head Injury

An RTA patient presents with GCS 15, vomiting twice, and amnesia. After admission to the orthopaedic ward, his GCS begins to fall.

How would you manage his patient?

ATLS approach:

A – Airway with C-spine control

This patient is likely to need intubation due to the low GCS, to optimise oxygenation and ventilation, and as a prophylactic measure to secure the airway if planned for transfer to a neurosurgical centre.

B – Breathing

- High-flow oxygen

- Look for chest injuries e.g. tension pneumothorax that may worsen CPP

C – Circulation

- Two large-bore IV cannulas

- Monitor BP

- Treat hypotension aggressively maintaining MAP > 90 mmHg as CPP = MAP - ICP

D – Disability

- GCS, if GCS < 8, call anaesthetics for a definitive airway

- Glucose

- Pupils

- Rapid neurological exam

E – Exposure

- Look for associated injuries, maintain normothermia

Call for senior help urgently

- Anaesthetics

- Neurosurgery

- Consultant

Investigations

- Arrange immediate non-contract CT head as vomiting + amnesia + deterioration → already meets criteria

Further management when CT confirms extradural haematoma

- Emergency craniotomy but management until surgery:

- Elevate head of bed to 30°

- Maintain oxygenation and ventilation

- Avoid hypoxia and hypotension as both worsen secondary brain injury

- Mannitol or hypertonic saline if signs of herniation (e.g., blown pupil)

- Consider ventricular catheter for ICP monitoring / drainage

- Admit to ICU for close monitoring

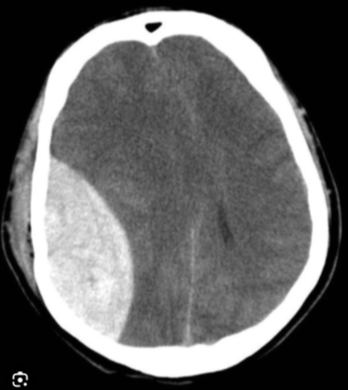

How does an extradural haematoma present on a CT head?

- Biconvex (lens-shaped) hyperdense collection

- Does not cross suture lines

- Causes mass effect with midline shift

- Compresses the adjacent lateral ventricle

- Often associated with a temporal bone fracture

- Acute blood appears bright white

What are the indications for immediate CT in head injury?

- GCS < 13 at any time

- GCS < 15 at 2 hours after injury

- Suspected open or depressed skull fracture

- Sign of basilar skull fracture e.g. haemotympanum, raccoon eyes, Battle's sign, CSF otorrhoea or rhinorrhoea

- Focal neurological deficit

- > 1 episode of vomiting

- Post-traumatic seizure

- Retrograde amnesia > 30 minutes before the impact

- Persistent headache or confusion

- Coagulopathy or on anticoagulants

- Dangerous mechanism of injury: Pedestrian struck my motor vehicle, ejection from vehicle, fall > 1 metre or 5 stairs)

- Age ≥ 65 with head injury

List some conditions where ICP monitoring is used.

Traumatic head injury, intracerebral haemorrhage, subarachnoid haemorrhage, hydrocephalus, malignant infarction, cerebral oedema, CNS infections, hepatic encephalopathy

Why do some head trauma patients develop a “blown pupil”?

A “blown pupil” in the context of head trauma occurs because rising intracranial pressure forces the medial temporal lobe to herniate through the tentorial notch. As the uncus is displaced, it compresses the oculomotor nerve at the point where the nerve runs along the free edge of the tentorium. This compression disrupts the parasympathetic fibres that normally constrict the pupil, leading to a fixed, dilated pupil on the same side as the lesion. As the herniation progresses, brainstem perfusion and function worsen, making the blown pupil a late and very dangerous sign of impending brainstem compression.

What is the Monro–Kellie Doctrine?

The Monro-Kellie doctrine states that the cranial compartment contains three components—brain tissue (80%), CSF (10%), and blood (10%)—and that the sum of their volumes is constant. Therefore, an increase in the volume of one component must be accompanied by a proportional decrease in another to maintain a stable ICP. This balance is crucial for normal brain function, but the body's ability to compensate is limited. Once the limit is exceeded and compensatory mechanisms fail and ICP approaches ~25 mmHg, even a small increase in volume causes a dramatic rise in ICP, leading to herniation risk.

Explain the relationship between MAP and CPP.

CPP = ((MAP::MAP = Diastolic + 𝟏/𝟑 (Systolic - Diastolic pressure)) – ICP

In normal physiology, as long as MAP stays within the brain’s autoregulatory range 50 to 150 mmHg, the cerebral vessels adjust their diameter so CPP and cerebral blood flow remain stable.

When MAP falls below the lower limit of autoregulation, the brain can no longer compensate. At this point, CPP drops in direct proportion to the fall in MAP, and cerebral ischaemia develops. Conversely, if ICP rises, CPP is reduced unless the MAP increases enough to offset it.

In practical terms, for a head-injured patient, even slight hypotension can be catastrophic because it sharply reduces CPP, while elevated ICP further compounds the problem. Maintaining MAP and controlling ICP are therefore essential to preserve cerebral perfusion and prevent secondary brain injury.

What is the normal ICP?

7–15 mmHg supine, and -10 mmHg when standing

How can you measure ICP?

Invasive methods:

- Gold standard: ((Intraventricular catheter::Most invasive method so carries a high infection rate and bleeding risk, may be difficult to insert, simultaneous CSF drainage and ICP monitoring is not possible)), allows CSF drainage

- Intraparenchymal probe

- Lumbar puncture, is rarely used due to risk of herniation and coning

Non-invasive methods:

- Transcranial doppler, assesses cerebral blood flow velocity

- Tympanic membrane displacement

What is the danger of lumbar puncture in increased ICP?

Performing a lumbar puncture in someone with raised intracranial pressure is dangerous because it can trigger brain herniation. When ICP is high, the cranial vault is already under pressure; removing CSF from the spinal canal suddenly lowers the pressure below the foramen magnum. This creates a pressure gradient that effectively “pulls” the brain downward. The cerebellar tonsils or parts of the temporal lobe can then be forced through the foramen magnum or the tentorial notch, compressing the brainstem. This can rapidly lead to loss of consciousness, respiratory arrest, cardiovascular collapse, and death. For this reason, an LP is contraindicated when raised ICP or mass effect is suspected.

In a ventilated patient, what simple manoeuvres can lower ICP?

- Brief hyperventilation to reduce PaCO₂, triggers cerebral vasoconstriction

- Elevation of the head of bed (~30°) to improve venous drainage

What are the strategies to reduce or maintain ICP?

To manage raised ICP, I begin with simple measures to improve venous drainage: Elevate the head of the bed to thirty degrees, keep the neck in a neutral position, and ensure nothing is obstructing the jugular veins.

Hyperventilation can be used briefly in emergencies to lower PaCO₂ and achieve cerebral vasoconstriction, but it must not be prolonged because it risks cerebral ischaemia.

To reduce cerebral oedema, I would give ((0.5-1g/kg mannitol::5-10ml/kg of 10% or 2.5-5ml/kg of 20% mannitol)) or small aliquots of hypertonic saline and maintain higher serum sodium at 140-145 mmol/l; 0.5-1mg/kg furosemide may be used as an adjunct.

To reduce cerebral metabolic rate for oxygen I ensure good temperature control, provide adequate sedation and analgesia, and treat any seizures promptly often with phenytoin 18 mg/kg. If ICP remains refractory, a thiopentone infusion may be used. EEG monitoring confirms burst suppression.

Throughout, I avoid hypotension and hypoxia to preserve CPP.

In a neurosurgical centre, an external ventricular drain allows CSF drainage and is very effective in lowering ICP. If there is a mass lesion, such as a haematoma, it must be evacuated urgently, and in selected cases a decompressive craniectomy may be required.

What is the Cushing reflex?

The Cushing reflex is a physiological response to dangerously raised ICP. As ICP approaches or exceeds the MAP, CPP begins to fail. In an attempt to preserve blood flow to the brain, the body mounts a sympathetic surge that raises the systemic blood pressure. This abrupt hypertension is then detected by baroreceptors in the carotid sinus and aortic arch, which respond by activating the vagus nerve. The resulting vagal stimulation slows the heart, producing bradycardia. As the ICP continues to rise and the brainstem becomes compressed, the respiratory centres begin to fail, leading to irregular or erratic breathing. The classic triad—hypertension, bradycardia, and irregular respirations—defines the Cushing reflex and represents an ominous sign of imminent cerebral herniation.

Why is there a lucid period after a traumatic brain injury?

A lucid interval in an extradural haematoma describes the period during which the initial loss of consciousness resolves and the patient appears relatively normal because significant bleeding has not yet accumulated.

The initial loss of consciousness is due to the immediate concussive effect of the impact rather than the haematoma itself.

After this brief concussion resolves, the patient often wakes up and appears relatively normal because significant bleeding has not yet accumulated.

Meanwhile, the arterial bleed—usually from the middle meningeal artery—continues under pressure, gradually enlarging the extradural collection. As the haematoma expands, it begins to raise ICP, compress the brain, and eventually cause neurological deterioration. This characteristic pattern is highly suggestive of an extradural haematoma and represents a neurosurgical emergency.

How can chest trauma significantly affect CPP?

Chest trauma can significantly impair CPP because CPP depends directly on the MAP and inversely on the ICP.

If the trauma involves major intrathoracic vessels, the resulting haemorrhage will reduce circulating blood volume and therefore lower the MAP, which in turn lowers the CPP.

If the chest injury leads to a tension pneumothorax, the patient will become hypoxic and hypercapnic; the rise in carbon dioxide causes cerebral vasodilation, increasing ICP and again reducing CPP.

In the context of a severe head injury, the patient may also develop shallow or irregular breathing as part of the Cushing response, worsening hypercapnia and further elevating ICP. The combined effects of reduced MAP and increased ICP drive the CPP down, placing the brain at risk of secondary ischaemic injury.

What are some symptoms and signs of raised ICP?

- Worsening, diffuse headache more severe in the morning or when coughing or bending forward

- ((Nausea and projectile vomiting::The vomiting centre in the brainstem is stimulated by the rising pressures))

- ((Drowsy, confused, reduced level of consciousness:::Due to impaired cerebral perfusion))

- Visual disturbance e.g. blurred vision, transient visual obscurations and, o/e papilloedema caused by swelling of the optic disc

- Defect in lateral gaze i.e. horizontal diplopia due to ((abducens CN VI palsy::Due to its long intracranial course and vulnerability to stretch))

- Unilateral dilated, unreactive pupil if uncal herniation compresses CN III

- Cushing’s △: Hypertension, bradycardia, irregular breathing

- Seizures, posturing, progressive neurological deficits